A hint of lawlessness: Lorongs of Wisdom by Geylang Adventures

Akanksha Raja

(Originally published on apublicsquare.sg - January 2020)

On a cursory skim through the Singapore Biennale programme, what stands out about this year’s edition is its eclecticism—it takes place across 11 venues from Far East Plaza to the National Library, and features names that one may not expect to encounter in the context of an art biennial, due to their more prolific work in other mediums, such as Pooja Nansi, who is linked more to the literary and slam poetry scene, or Ryuichi Sakamoto, who is more of a musician and performer. Extending the reach and appeal of the Biennale outside of the art world echo chamber of museums and white cubes is strongly emphasised in the Biennale’s programming, which makes it feel more like a dynamic, multidisciplinary festival akin to the Night Festival. One of the features of this “festival-seminar model” (as described by artistic director Patrick Flores) is the Coordinates Projects series, which comprises seven tie-ins with arts companies or community organisations such as the Indian Heritage Centre, Drama Box, Intercultural Theatre Institute, and Casco Art Institute. The projects facilitate various modes of direct connection and exchange with specific communities and spaces.

One among the Coordinates Projects is Lorongs of Wisdom, a Biennale-special edition of the walking tours organised by Geylang Adventures through the titular neighbourhood, which have been taking place since 2014. I had never been, but had read rave reviews of this and other programmes run by its enterprising young founder, lifelong Geylang resident Cai Yinzhou. Having arrived early at the meeting point in the carpark of Healthserve on Lorong 23, I chatted briefly with Yinzhou and co-host Weng Wanying about the Biennale collaboration, which they described as a challenging new endeavour for them with having to reconfigure the tour in line with the Biennale programme, mentioning that in this version the sites would be “interpreted differently”—since I hadn’t attended the regular sessions I couldn’t tell exactly what these differences were. It was nevertheless an enlightening and enjoyable evening for a lifelong Jurong resident discovering a neighbourhood so very far away and dissimilar.

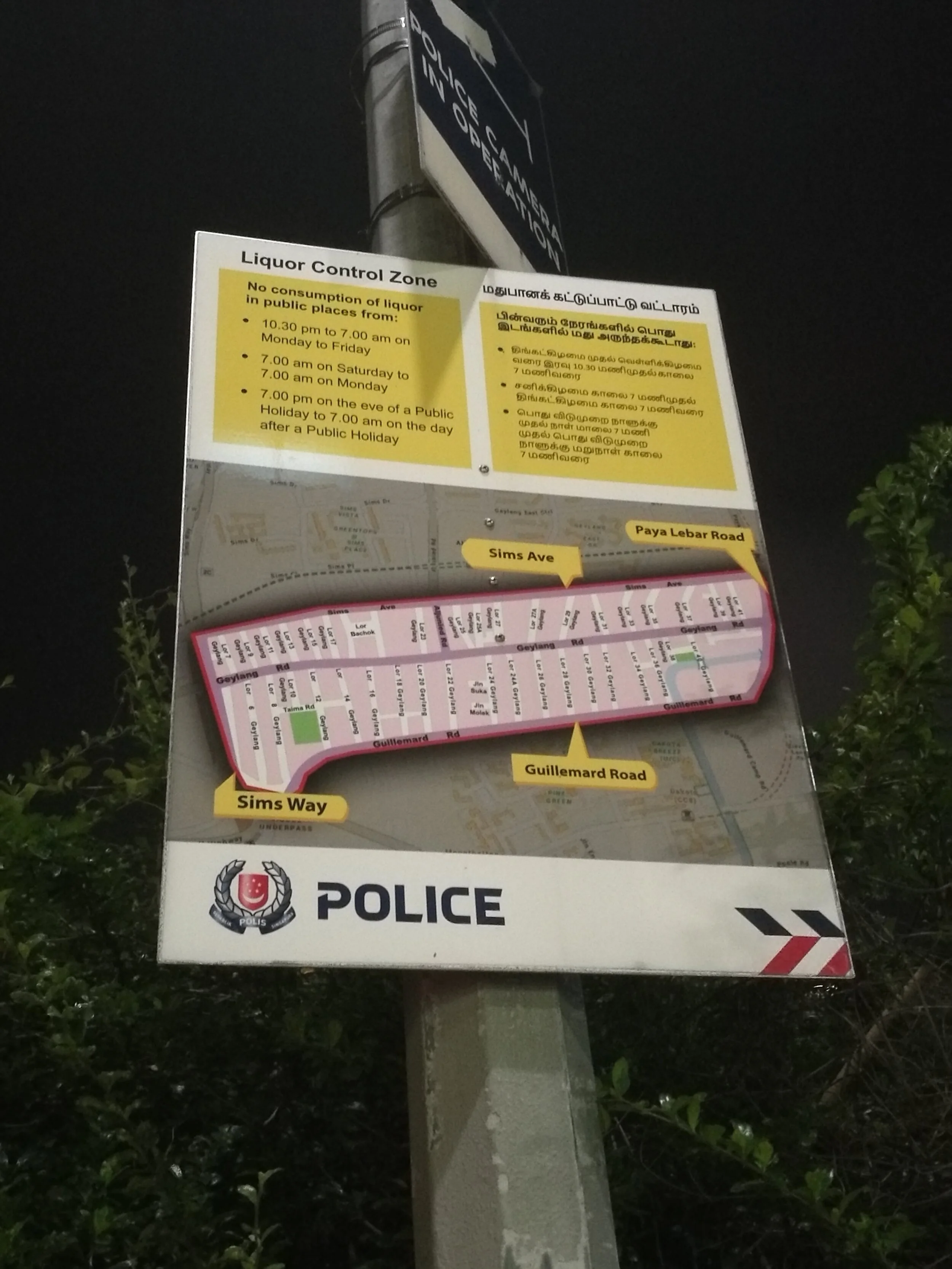

The genesis of Geylang Adventures arose in the aftermath of the Little India riots in 2013. The riots, having involved hundreds of migrant labourers, catalysed growing social concern about the increasing presence of migrant workers in the country. The police put out a statement that Geylang was more of a hotbed for crime than Little India or any other locale. The Liquor Control Act was implemented in 2015. More surveillance cameras were installed around the neighbourhood. With heightened scrutiny and censure of the neighbourhood, Yinzhou was motivated to start Geylang Adventures as a way to shed light on Geylang’s history, how it has come to be what it is, and change the widespread stigma around the area and the communities that call it home.

Healthserve and the Migrant Worker Community

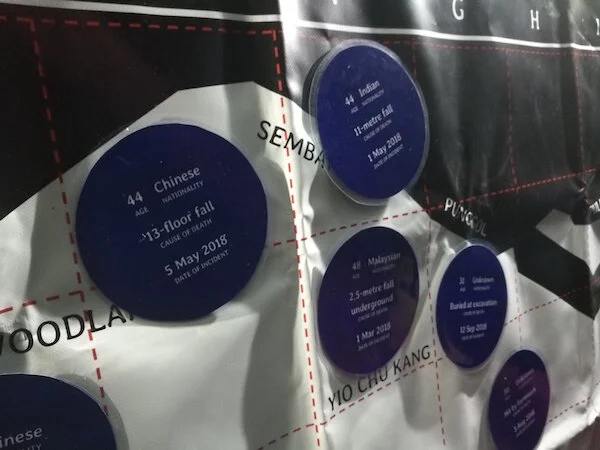

One of our first stops is Healthserve, a non-profit organisation that helps migrant workers get access to regular health checkups and necessary medical care in times of need. In the middle of the courtyard, Yinzhou unravels an illustrated map of Singapore and invites participants to affix placards bearing location names of various worksites. On the reverse side of the placards are statistics of migrant worker deaths at their respective worksites. The names of the dead are never made known, and we are reminded of the relentless invisibilising of the migrant worker community in media and in everyday life, through stigma, exploitation, and the reducing of their lives to nameless statistics.

But there is an uplift to this segment of the tour—a tree stands at the corner of the courtyard adorned in tiny lights and bearing postcards with the names and personal stories of the migrant workers that Healthserve had managed to successfully assist in times of serious medical need.

Later on during the walk, we head into an alleyway behind Lorong 24A, where we see a fallen badminton net on the ground. I assume it’s meant to be replaced, but it turns out that it’s just a melancholic memento of how Backalley Barbers began. Yinzhou, who used to join migrant worker friends in the area to play badminton, recounts being approached by the police one day in 2014 to be told that they were not allowed to gather in public spaces to play badminton any more—doubtless a cautionary stance, in the wake of the Little India incident, against the public gathering of foreign workers in a high-crime neighbourhood. Seeking another way to spend meaningful time with his friends, Yinzhou conceived of Backalley Barbers, which gives free haircuts to migrant workers.

Sin and Salvation

As we pass by sex-enhancement drug peddlers on our way across the road towards Chong Tuck Tong Temple, Wanying shares that Geylang has the highest concentration of religious establishments of any neighbourhood in Singapore—a fact that would seem unlikely given Geylang’s reputation, and was new and intriguing to me as well as other Singaporeans in the group. We enter the Buddhist-Taoist temple, remove our shoes and take our seats in the prayer hall, as the voice of Alan Chong, the temple’s young custodian, narrates the temple’s history through the speakers. Later he enters, carrying a pottery wheel and clay with him. He sits in front of the altar, sets the equipment in front of him and begins making a series of pots of varying shapes and sizes, as a different voice comes on the speakers describing the symbolism of each shape of pot. I tune out the narration after some time, because it veers into platitudes about unity in diversity and such. Instead, I am pondering how the extensive presence of religion in Geylang relates to the local residents of the neighbourhood reputed for so much vice.

Alan shares that religious establishments do play a significant role in the lives of the neighbourhood’s residents. Many see them as places to cleanse themselves of the negative energy they’ve incurred engaging in crimes, drug use, or gang activity. Sin and redemption coexist. Listening to stories of residents finding a source of healing in the many religious institutions in the area, I find my impression of Geylang altered somehow, softened perhaps, and it becomes a little clearer to me why the neighbourhood is referred to by Yinzhou as an ‘ecosystem’. Despite being the black sheep of Singapore’s neighbourhoods, the most surveyed, patrolled, and scrutinised, the most ‘broken’, Geylang contains a sense of self-sufficiency and peaceful coexistence of interdependent opposites.

_

Lorongs of Wisdom by Geylang Adventures runs on various dates in February and March.